Dense fog hugs the asphalt. A Cessna jet rushes overhead, its landing lights only at the last moment penetrating the clouds over Kassel-Calden airfield in central Germany. Despite the hazy weather, I would have happily camped here last night with a tent and a can of ravioli to avoid being late. Because today this now-abandoned runway is a heaven for car fans.

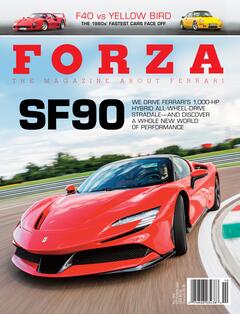

The first is perhaps the most famous bedroom-poster car of all time: the Ferrari F40. The second is the car that put the F40 in its place during a top-speed run in Italy: the Ruf CTR, better known as the Yellow Bird, which is just now rolling off a closed trailer. Then the delivery crews head off to have a coffee in the terminal, and I’m suddenly alone with the two hottest cars of the late 1980s. It’s kind of unreal.

My eye initially wanders along the bright yellow body of the Porsche 911-based CTR (which stands for Group C Turbo Ruf), the machine that emphatically hammered home the name Ruf into all gearheads’ collective consciousness. Back then, the boys around Alois Ruf packed a twin-turbo engine pumped up to a claimed 469 hp into the narrow body of a 911 Carrera (rather than the generously flared Turbo) with the aim of thoroughly trouncing the competition.

And they succeeded: On the high-speed course in Nardo, the Yellow Bird hit 213 mph—12 more than the F40, the first production car to clear the 200-mph barrier. When the bright yellow explosive device passed the light barrier, it was clear to car writers at the time that there was much more to the Ruf than met the eye. Its front spoiler and missing rain gutters depressed the drag coefficient to a respectable 0.32, but at least 500 hp would be required for such a top speed.

500 hp? The Yellow Bird certainly doesn’t look like it packs that kind of power. It looks almost harmless. Only the bright yellow hue helps it not to be visually eclipsed by the aggressive, rugged, functional shape of the F40. But appearances are deceptive. This is not a 911 for the cozy Sunday classic rally: The CTR was the fastest road-legal car in the world in its day, and it remains the fastest classic car in the world today. And now it’s time to drive it.

After I thread behind the steering wheel and pull the thin door closed, some things at first seem very familiar. The view over the cannon-barrel fenders, for example, and the 911’s classic five round instruments. Ruf even left the Blaupunkt cassette radio in place. But there are differences, too, including a speedometer that goes to 350 km/h [217 mph], a roll cage, and a Recaro seat that grips my hips like a vice.

Ferrari’s twin-turbo V8 pumps out 478 ponies but F40 tops out at 201 mph.

I turn the ignition key to the left and the extensively modified flat six out back starts up in a mostly unspectacular manner. The gears of the Ruf-developed five-speed ’box are sorted by a long gear stick, which mushrooms out of the gimbal. First gear is back and to the left, and it takes a moment to find the coupling’s optimal grinding point, then I head onto the airfield for a leisurely lap.

After warming up the car carefully, I pick up the pace. When cornering on uneven asphalt, the front end quickly becomes restless, the steering uncomfortably playful; when I apply the brakes, I can feel the engine pushing in the rear. Everything is so typical of a late ’80s 911. The fastest car of its time? It doesn’t feel that way.

Now the engine is at operating temperature, and I give it full throttle. 3,000 rpm, 3,500, 4,000, nothing happens. I glance down at the adjustable boost controller between the seats, and that’s when it happens—Thor’s hammer hits me in the balls. The Ruf crouches and zooms down the straight as if someone had pressed the fast-forward button: VROOOOAAAAM! Hissing! Scary!

At 124 mph, I pull the rip cord. What’s left? I’m stunned that something so old can be so fast. Without all the new fashions like carbon-ceramic brakes, rear-axle steering, dual-clutch gearbox, anti-lock brakes, traction control, it’s fully analog. And fully awesome.

The Yellow Bird’s brakes came from Group C. Because there was no suitable tire format for the CTR in 1987—apart from oversized Pirellis for Ferrari and Co.—Ruf and Dunlop developed a special tire, the “Denloc,” with the necessary speed rating.

Only 29 CTRs were built, each with its own Ruf chassis number. Porsche delivered the bare 911 body shells to Ruf, which was the official manufacturer. The doors and trunk lids were made of aluminum, while unnecessary ballast was thrown out. A back seat? Insulation material? Please, no one who wants to be quick needs those.

Ruf’s twin-turbo flat-six engine makes a claimed 469 hp, good for a top speed of 213 mph.

Back to the runway. I sample Thor’s hammer again— VROOOOAAAAM! —then quickly take a cool-down lap, because the second car is already waiting.

FOR US CHILDREN OF THE 1980S, the F40 was a kind of people’s car. Everyone had one. Okay, on my example you couldn’t open the doors, and the body was made of injection-molded metal instead of carbon-fiber reinforced plastic. But unlike Play-Doh and Tamagotchi, it was an educational toy, since it had a decisive influence on my choice of profession.

Now the Ferrari sits in front of me, full-scale and with opening doors. Its body is furrowed with ventilation openings, and at the rear the basket-handle spoiler protrudes toward the sky. The paint was so thinly applied by the factory that the bodywork’s composite weave remains visible.

The famous slotted Plexiglas cover obscures the F40’s engine. Led by chief engineer Nicola Materazzi, the engineers expanded the V8 used in the 288 GTO to just under three liters and stoked the short-stroke engine with two IHI turbochargers maxing out at 1.1 bar, or 16 psi.

When Ferrari carried out the final test drives with the F40, the project was still listed under the code name “Le Mans.” At that time, the Scuderia was only a modestly successful racing team, one whose last great sports-car successes had come at La Sarthe. Others were at the forefront, on the racetracks and, from 1986, on the road—especially Porsche, whose 959 was offered to the international aristocracy. A new supercar was needed to put Maranello back on the map, and the F40 became Enzo Ferrari’s final statement, the last street car he would give his blessing to.

After overcoming the wide sill and sliding into the bucket seat, I’m treated to surroundings mostly familiar to those who hold an FIA Super Licence. Some felt carpet on the dashboard contributes a pinch of cuddle factor, but Ferrari elected to leave the F40’s interior aesthetics in their purest, structural form.

At the push of a button, the beast wakes up in the rear. Or not? Contrary to expectations, there is no infernal thunderstorm, only a dull rumble that gives a vague idea of what’s to come.

Around 3,500 rpm, the F40 is almost tame. But woe to those who let themselves be surprised by the massive boost in performance that the biturbo V8 then releases on its 335/35ZR17 rear rollers (a full 80 millimeters wider than those on the Yellow Bird). Then Enzo’s last opus wildly wags its tail in search of grip, paints black lines on the asphalt, and catapults its crew towards the curvature of the earth. Or also straight out of the curve. The rear wheels have as much grip on full throttle in first gear as the rear legs of a startled dachshund on a freshly polished parquet floor. A lot of power is also required to apply the clutch and brake, though this must of course be supplied by the driver.

Only a thin plastic wall separates the occupants from the engine, whose aggressive bellowing is omnipresent. Intake and exhaust noises, the hissing of the wastegate, not to mention the hard blows to the undercarriage from rocks and road debris or the “click-clack” as I shift gears. All this gives me a feeling of being at one with the car. And did I mention the V8’s responsiveness (once on boost) and torque are amazing?

The F40 embodies an early take on the modern supercar, one without hybrid battery power, Formula 1-inspired paddle shifting, or stability control. The acceleration orgy only ends at 201 mph, the V8’s 478 hp and 425 overflowing lb-ft not having much trouble moving the 1,100-kilogram unladen weight. The F40 pulls the wrinkles from my face and almost squeezes the air out of my lungs; the sprint to 200 km/h takes 2.3 seconds less than in the Porsche 959. It would have been the world’s fastest car, but for the Yellow Bird.

Time to stop. I open the door by pulling a wire rope—there’s no handle—peel myself out of the seat, and climb out over that sill. The photographer is back in a flash, taking more and more detail photos. It’s no wonder; these two cars are not short of interesting perspectives.

The trailer is already rolling in to take the cars back. The fog has disappeared, warm sun rays penetrating the clouds. If the Ruf and Ferrari were ’80s stars made of flesh and blood, if they were called Madonna or Prince, I would ask for autographs. Instead, I can only gaze again in wonder and stroke the silhouette of the F40 one last time. Yes, the doors still open; it wasn’t a dream.

The Yellow Bird, the fastest car of the 1980s, fascinates to this day. Its narrow body looks innocent, but the truth is revealed when the turbo hammer falls. The F40 is a disguised racing car, a milestone in automotive history, and a dream machine to this day. It is also one of the top-ten cars you have to drive once in your life.