Italian racing driver Franco Scapini enjoyed an impressive professional career, one that saw him ascend through the ranks from karts to Formula 3 to IndyCar, endurance race a Lancia LC2 in the glorious Group C days, and peak as a test driver for the Life F1 team. But by the end of the 1990s, in his mid-30s, he’d left the tarmac behind and forged a new and very successful career in Formula 1 Powerboat racing.

Scapini’s father had other ideas, though. A Ferrari dealer and official service center owner for 30 years, he, unbeknownst to his son, had been talking with his business partner about buying and running an F355 Challenge. The man they wanted behind the wheel, of course, was Scapini—but unlike most people, he turned down the opportunity.

“I didn’t want it!” Scapini recalls with disdain. “A Challenge car in the middle of the 1990s wasn’t much more than a road car with a roll cage and slick tires, so it wasn’t interesting to me at all.”

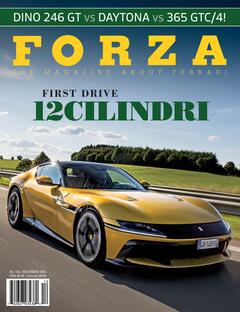

The Ferrari at Daytona in 1999, followed by Riley & Scott prototype.

His father’s partners eventually managed to persuade him to race, and s/n 104675 was quickly entered in the 1997 Italian Ferrari Challenge. Over the course of the year, Scapini finished on the podium several times, but it was far from the highlight of his career.

“It was very easy to get to the limit of the car, so if you have half of the grid who can drive it to the maximum, for me that is not really the spirit of racing,” he explains. “I really drove without wanting to.”

Scapini wasn’t alone in wishing the car had more performance, but while some competitors talked about turning the F355 Challenge into a bona fide race car, he was the one who would actually make it happen. With the Michelotto-built 348 GT/LM becoming a little dated and a new 360 GT3 still a few years away, Scapini felt certain an F355 GT3 would fill the gap. So he recruited two friends, Stefano Bucci and Andrea Garbagnati, who had entered the 1997 24 Hours of Daytona in a rented Camaro just for fun, to help make it happen.

At the time, Michelotto was busy developing the 333 SP and wasn’t interested in doing anything with an F355, so Scapini approached Ferrari. While the company didn’t offer to help in any official capacity, it did allow him to use the Fiorano test track to test the car once it was up and running. This opportunity to demonstrate his engineering capabilities to the top brass at Maranello was something Scapini accepted gratefully.

WITH BUCCI AND GARBAGNATI PROVIDING FINANCING, it was up to Scapini to build the car. The first thing he did was put the rather portly Challenge-spec F355 on a crash diet. The minimum weight limit for the FIA GT3 class was 1,140 kilograms, or 2,513 pounds, and the Ferrari weighed in some 573 lbs. over that minimum.

Scapini applied his experience in making carbon-composite racing boat hulls to building carbon-fiber and carbon-Kevlar panels for the F355, and the weight came off quickly. For example, where the original steel engine cover weighed 62 lbs., its carbon-fiber replacement weighed just 13. The original glass between the cabin and the engine bay weighed 13 lbs., but a new Lexan window weighed just two. Many other parts were built from composites, including the doors, front hood, front bumper and splitter, flat underbody, and the huge rear diffuser.

From a young age, Scapini had been interested in aerodynamics, and for the F355 he spent a long time carefully studying what other manufacturers, especially Porsche, had done to their GT3 cars. In addition, he relied on his experience in designing and building competition catamarans.

“In a boat, you need to exploit the fluid dynamic laws both to the tunnel under the boat and the two decks,” he says. “Negative pressure and positive pressure, downforce and lift, etc. And that’s what I did with the F355.”

Turning the Challenge car into a full-on GT3 racer involved a serious amount of mechanical engineering work, as well. Class rules allowed Scapini to move the Ferrari’s suspension pick-up points 30 mm (about 1.2 inches) in any direction, but doing so required abandoning the stock suspension members in favor of fabricated A-arms. Since there was no similar car extant to copy, Scapini used CAD and physical mock-ups to work out the geometry from scratch. New shock absorbers with separate nitrogen tanks were fitted, new anti-roll bars were developed and built, and much more.

Engine upgrades included a new intake system that featured eight individual throttle bodies. The exhaust manifolds and exhaust pipes were replaced with custom large-bore versions and all four cams were replaced. With so many components changed from the original design, Scapini sourced a bespoke engine management system from Italtecnica.

With the major changes out of the way, Scapini turned his attention to the smaller items. First up was the steering.

“I needed the steering wheel to be closer to the driver,” he recalls. “I also wanted to be able to run the car with the power steering pump off. I never drove a race car with power steering, which is quite normal for professional drivers, but with gentlemen drivers in the team, they need the help as they’re not fit or strong enough to be able to do too many laps without power steering. It was operated via an electrically controlled hydraulic pump from a switch on the dashboard.”

Scapini (with headset) and Ivan Capelli at Vallelunga in 1999.

Another significant change was to the braking system. The stock ABS and brake servo were replaced by a new system with separate hydraulic pumps for the front and rear axles, allowing the driver to control brake bias from the cockpit. More challenging was moving the water and oil radiators from their original position on the sides of the car to the front, where vents in the hood helped extract the hot air. Then it was time to replace the five-bolt wheel hubs for hubs with a single locking nut—in this case made out of Ergal, a 7075 aluminum alloy, which also underwent an anti-seize treatment.

“I made the hub from special aeronautical steel, the same type used to make helicopter blade rotors,” Scapini explains.

From the initial idea to the car’s first test took just five months—a lightning-fast time considering Scapini did almost all of the work himself. The goal was to compete at Daytona in 1999, so in 1998 Scapini entered several races in the Italian, French, and Spanish GT Championships. He came away with several class wins and even some overall podiums, ahead of the supposedly much faster GT2 machinery.

Sadly, even though everything had started out as a pro-ject between friends to race a Ferrari at Daytona, it didn’t work out that way. Despite the success Scapini was having with the car, Bucci and Garbagnati weren’t convinced the Ferrari was going to be competitive, or reliable enough, in the gruelling race, so they arranged for a test driver to give it a thorough shakedown. After a full day behind the wheel at a local circuit, the driver provided a long list of changes and upgrades he thought were needed before they went to the USA.

“It would have been very expensive and time-consuming to do everything, so I asked him if he was really sure,” says Scapini. “He insisted that he was right, but I still didn’t agree, so I got in and was two seconds a lap faster than he’d gone all day. I asked him if we could stop now or if he wanted me to go even faster.”

Just to drive the point home, a few days later, at the same track, Scapini raced the car in the Italian GT Championship, finishing third overall and easily winning the GT3 class. Bucci and Garbagnati still decided to rent a Porsche to race at Daytona, but Scapini remained determined to go to the race in the car he’d designed and built specifically for it.

Fortunately, thanks to his contacts and reputation, there was no shortage of drivers willing to pay to join him behind the wheel. Ferrari Challenge racer Pier Angelo Masselli signed up, and was joined by OMP sales manager Marco de Iturbe, and former Italian Touring Car racers Gianni Biava and Gian Luca De Lorenzi.

The quintet performed well in Florida, but after eight hours the Ferrari ground to a halt when its clutch bearing disintegrated. It took the mechanics more than three hours to fix the car, but the team was still classified as finishing the race—although 12th in class was not what they’d been hoping for. Still, the potential of the project and the speed of the car were proven during the night, when Scapini set several fastest laps in the wet. He credits that performance to the effectiveness of his aerodynamic work.

In 2000, keen for a good result, Scapini cut down on pay drivers and entered himself, friend and former F1 driver Ivan Capelli, Masselli, and Ferrari Challenge stalwart Eric Prinoth in the race. He shipped the car over to Florida with high hopes, but they were dashed immediately—on the first lap of the opening free practice session, Prinoth slammed the F355 heavily into the wall.

The team lost all of the available setup and practice time to rebuilding the Ferrari, a task they finally finished just a half-hour before qualifying. Scapini had gone from expecting a good result to facing a challenge just getting the car onto the race grid, yet he still managed to qualify 79th out of 89 starters.

The Ferrari ran well until halfway through the race, when the engine began surging and stalling. Back then, teams didn’t have laptops to plug into their cars and read the sensor fault codes, and it took so long to diagnose the problem there was no hope of a good result. It turned out to be the sensor that read the throttle bodies’ butterfly position, which tells the fuel pump how much gasoline to send to the engine.

There was still a lot of untapped potential in the car, but by this time Michelotto was almost ready with the new 360 GT, so Ferrari asked Scapini to stop development. In 2001, he sold the F355 to a Belgian customer. It was fielded by Mastercar SRL at Daytona one last time, but didn’t manage to qualify.

After that, Scapini lost track of the Ferrari. It was never raced again, but last year it was purchased by classic-car broker Jan B. Luehn. Scapini was invited to recondition the car to be eligible for historic racing, it needing a more modern roll cage. Apart from that, he says, this unique F355 GT3 remained in the same ready-to-race condition it was a quarter-century ago.