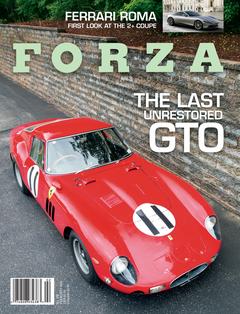

Cracked, flaking, and peeling, the crimson red paint on this Ferrari clings to the alloy bodywork for dear life. After five decades, it’s a losing battle but—given this car’s regular use, including on tracks like Sonoma Raceway, where we encountered it at the inaugural Sonoma Speed Festival in early June—an exquisite one, a fight that will hopefully not end anytime soon.

Of course, the fact that the Rosso Cina paint adheres to a 250 GTO makes the slow decline all the sweeter. The car’s patina is truly something to behold.

Long Island resident James McNeil, who’s owned this ex-John Surtees Ferrari (s/n 3647GT) since 1967, still tries to treat his unique (it’s the only GTO never to be restored) and extremely valuable (another example sold for $70 million in 2018) car like the racing machine it was built to be. McNeil wasn’t interested in an investment back in the late ’60s, and he still doesn’t see the Ferrari as such; he wanted to buy the model that had been driven to three GT Manufacturers Championships in a row, from 1962 to ’64. The GTO’s low, slippery shape and cutting-edge rear spoiler made it much faster in a straight line than its competition, including the Shelby Cobra. It was the premiere sports car of its time.

John Surtees drove the GTO (wearing #85) to third place at Snetterton in 1962. (Photo courtesy Revs Institute)

An aspiring racer, McNeil wanted to purchase a competitive car, one that would bring him success at tracks like Bridgehampton, which was close to where he then lived on Staten Island. He had previously owned two other Ferraris—a Tour de France and a Cal Spyder—so the GTO seemed a natural step.

However, since Ferrari only built 36 Series I GTOs, his quest wouldn’t be an easy one. On the other hand, it wasn’t as if he was facing a lot of competition. Says McNeil, “Remember, back then there were but a few who had any interest in old race cars.”

In December 1966, he found his quarry listed in the classified section of the Sunday New York Times. The ad simply read: “For sale 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO. Race or road. Massachusetts registration.” McNeil had hit the jackpot. Not only was his desired vehicle listed in what amounted to his local paper, it was located in Springfield, a mere 100 miles away.

S/n 3647 had been first purchased in June 1962 by Colonel Ronnie Hoare, founder of British Ferrari importer Maranello Concessionaires. In conjunction with the Bowmaker racing team, Hoare entered the GTO in five UK races during the ’62 season. Driving duties were given to future Formula 1 World Champion John Surtees, who earned a trio of third-place finishes.

Later that year, the Ferrari was sold to Zourab Tchkotoua, a Russian prince living in exile. Tchkotoua drafted Surtees and fellow Brit Mike Parkes to race s/n 3647 at the 1,000-kms of Paris at Montlhery that October. They finished second, and the GTO still wears the same number 11 it wore on that successful outing.

The only potential off-note for an American buyer was the Ferrari’s right-hand-drive layout, but the placement of the controls was not an issue for McNeil. So, after negotiating the price, he bought the car from Robert Sauers, its eighth owner. While this was McNeil’s third pricey Ferrari purchase, he was not a man of means; he needed to finance the $7,000 acquisition, which he calls “the price of a Cadillac Fleetwood.” Though it was a lot of money for McNeil, he still got a good price; after all, Ferrari charged $18,000 for a new GTO in 1962.

Original 300-hp, 3-liter V12 has been rebuilt once during s/n 3647’s life.

Deal done, McNeil drove the Ferrari back to Staten Island. On the way, he remembers thinking, This is a lot of car for the road. Three-hundred-horsepower automobiles may be a dime a dozen these days, but back in 1967 that much output was significant; even 289 Cobras missed the mark by about 30 hp. When paired with a chassis that weighed at least 1,000 pounds less than American muscle cars of the era, the Ferrari’s 300-hp 3.0-liter V12 engine made it a veritable supercar.

It was a different story on the racetrack. By the time McNeil bought the GTO, it was no longer the sports car to have; the bloom had come off the rose. There were cars with bigger engines, including Ferrari’s own 4.0-liter version. The Shelby Cobra Coupe met the GTO on the aerodynamic front and outgunned it on horsepower, taking the GT Manufacturers Championship in 1965. Then came the mid-engine onslaught, with ultra-low-slung machines like the Porsche 906. Though still unquestionably fast, the GTO was no longer a championship contender.

“It’s time was gone,” McNeil says. “All it was good for was SCCA racing.”

The factory fitted this leatherette interior in the mid-’60s, reportedly before trying to sell the car to John Surtees.

As things turned out, McNeil didn’t end up racing the GTO—at least, not initially. Instead, he drove it on the road. He drove it to car events. He drove it to Manhattan. “I just drove it around,” he explains.

On one early morning drive to New York City from Staten Island, recalls McNeil, the toll taker at the Verrazzano-Narrows bridge, wide-eyed at seeing the sleek Ferrari pull up to his booth, implored him to “gun it.” He obliged. Thanks to its high cylinder and carburetor counts—six of the latter, Webers naturally—the Ferrari sounded like no other car on the road. With a glorious, high-pitched wail emanating from its long side pipes, McNeil’s GTO surely made a lasting impression on that toll worker.

S/N 3647 FINALLY RETURNED TO THE TRACK in the early 1990s, when McNeil and wife Sandra began vintage-racing it. They mostly entered East Coast events through the Vintage Sports Car Club of America, competing at circuits like Lime Rock in neighboring Connecticut. They loved the way the car handled, the way it felt light on its feet. With its tubular steel frame and thin, aluminum bodywork by Scaglietti, the GTO weighs in at just 2,100 pounds. Thanks to the Ferrari’s handling balance, they found it to be a very forgiving car to race, especially compared to the 289 Cobra they had also acquired by that time.

Targa Florio entry sticker still in place after 54 years.

“You can do stupid things and the car will pull you through, nine times out of ten,” McNeil says, quickly adding a quote he attributes to Surtees: “‘This car makes any driver look good.’”

One way to make the GTO even more competitive on the vintage-racing circuit would be to fit it with soft-compound tires. McNeil has experimented with this in the past, but while it made the Ferrari faster the resulting higher lateral acceleration was too much for the Borrani wire wheels. “I kept breaking spokes,” he says. As it is, the Borrani wheels currently on the car are spares that he sourced 25 years ago—the originals were carefully stored away—wearing what he calls “crappy,” hard-compound Dunlops.

By the early 2010s, McNeil had stopped driving the car himself, but that didn’t keep s/n 3647 off the track; Sandra took over the right seat full-time. “She does most of the driving now,” he says. “She’s a better race-car driver than I am. You don’t want her in the car behind you!”

Sandra has been racing since her mid-30s. She started with skiing in the ’60s, and jumped at the chance in the early ’70s to try her hand in a Formula Ford. “I ate it up!” she recalls, first learning the craft at the Skip Barber Racing School at Lime Rock.

She continues to work hard at what she calls her favorite hobby, regularly going to the gym and putting in extra training before races. The secret of her on-track success? “I wait for people to get tired,” she says, “then I’m ready to pass them. I’ll compete as hard as any guy can.”

True to form, 79-year-old Sandra passed six cars during the Group 3 race at the Sonoma Speed Festival. It may have helped that Sonoma Raceway is her favorite track, but what certainly didn’t help is that she doesn’t fit in the Ferrari. “The car and I are not well suited,” she says. “I’m too small.”

Sandra needs multiple pads to get her close enough to the steering wheel and pedals. However, this position still leaves the gear lever a long reach away—a shame, since the gated shifter’s placement and action are usually much admired by drivers. The mirrors are too small, too, and since the McNeils refuse to fit larger, non-original ones, it’s hard to see competitors attempting to pass. Given the car’s value, it’s easy to understand the anxiety Sandra experiences when jockeying for position on track.

“The GTO is the only car that I’m apprehensive about sliding around a corner,” she admits. The only time she can really enjoy herself is on the straights, which is when she’s able to execute most of her passes thanks to the V12’s hearty output. “I’ve got the power,” she says with a satisfied grin. “It’s a thrill.”

The straights are also where she can most appreciate the Ferrari’s storied exhaust note, which she likens to a “symphonic orchestra.” In addition to the power and the music, another attribute helps Sandra look past her fitment issues with the GTO: “It has a soul,” she says.

S/n 3647 on track at the 2019 Sonoma Speed Festival. (Photo by Dennis Gray)

OFF THE TRACK, the McNeils’ GTO looks like no other. While the paint is the most noticeable aspect of its rich patina, there are numerous details that speak to its unvarnished state.

Take its weathered Targa Florio sticker as an example. Located on the lower corner of the driver’s side of the windshield, this visible bit of race history was affixed to the car in 1965—nearly 55 years ago. The GTO’s fifth owner, Roman Tullio Sergio Marchesi, entered the car in the Italian road race, sharing driving duties with Enrico Mosca, who briefly owned the car before Marchesi. The pair failed to finish the grueling event, the same fate that had befallen Mosca the year before, when he drove it for then-owner Mennato Boffa. Regardless of results, the fact this Ferrari was twice driven in earnest on those tortuously winding Sicilian roads, through those enchanting villages, gives s/n 3647 a special aura. Stare at that Targa Florio sticker for a few moments and you can feel the history emanating from the Ferrari.

As has been McNeil’s wish since 1967, his GTO still looks like a well-used racing car. To say it is still all-original would not be entirely accurate, because, as with most racing cars, the Ferrari suffered its share of trackside accidents back in the day, some of them requiring body and paint repairs. According to McNeil, the Ferrari was crashed multiple times, ending up on its roof at least once. For instance, Surtees tangled with an Aston Martin at the Tourist Trophy Race at Goodwood on August 18, 1962. Though a photo shows the DB4 Zagato (s/n 0183/R, which sold for $13.3 million in 2018) looking in worse shape than the GTO—the Ferrari apparently having rammed into the Aston’s rear three quarter—both cars were DNFs.

James McNeil bought his GTO in the late 1960s. More than 50 years later, wife Sandra still races it. (Photo by William Edgar)

“That’s the fate of race cars,” says McNeil. “If a car has never been hit, it’s probably never been raced.”

No one knows that adage more than race-car drivers, which makes it interesting to ponder the fact that, according to McNeil, Enzo Ferrari attempted to sell this GTO and two others to Surtees at the end of the ’65 season. McNeil says that, in a bid to make the car more presentable, Ferrari had a street-friendly leatherette interior installed in s/n 3647, which remains in place today. Ferrari offered to sell the cars to Surtees for $6,000 each, but the driver, who won the Formula 1 World Championship for Maranello in 1964, balked, reportedly telling Enzo, “You don’t pay me enough.”

Though s/n 3647 has not been restored since 1967, it has been lovingly maintained. McNeil entrusts his GTO to the sympathetic hands, eyes, and ears of Andrew Funk in Rhode Island—who, according to McNeil, says things like, “That motor is talking to us, we better listen.” Other than making beautiful music, though, the 3.0-liter V12 has had very little to say over the years. It has been rebuilt once, about halfway through its lifetime. Since then, several thousand hard miles have been put on the engine, consisting of roughly 25 vintage-race weekends and the 250 GTO Reunion at Pebble Beach in 2011.

Though McNeil admits to being tempted by the restoration siren from time to time, he has not given in. He has, however, occasionally allowed touchup paint to be applied, but only sparingly and only by a friend who happens to be what he calls a “world-class pinstriper.”

“I hate to see the bare aluminum shine through,” he notes, pointing out that no primer was applied before the GTO was painted back in the day.

McNeil sees restoration as a vicious cycle that should be avoided if possible. “Nobody can leave things alone, which is what I did,” he says. Glancing over at a perfectly restored vintage Ferrari parked near his GTO in the paddock at Sonoma, McNeil remarks, “That’s not a race car. Anybody can do that; all you have to do is sign checks.” Tapping on his Ferrari proudly, he concludes, “This is 52-year old paint.”